Producing Without Reproducing

They say no one makes anything in America anymore and this has been the case for a generation or two. While most people recognize that as an exaggeration, it is hard not to look at the decline of former industrial powerhouses like Detroit and Baltimore and not feel as though manufacturing has fled the country. It doesn't help that governors crow over the opening of factories employing a few hundred workers and promote these developments as great successes in their plan to bring "good middle class factory jobs back to American soil." The truth is more complex. It always is. Moreover, since my thoughts wander toward the future of our society, I speculate that the truth hints at what may be by turns dismal, Utopian and ultimately catastrophic. I should have something to say for myself, and I do.

Common knowledge tells us that developing nations have weakened US industrial might by employing cheap labor. American factories paying American wages and benefits cannot compete with the labor of the millions who earn cents on the hour and receive few if any benefits. This assessment is largely accurate, but it describes an unstable dynamic. Labor costs in the West are so high because we are a victim of our own success. Well I suppose victim isn't the right word here. With rising economic development comes a better standard of living. Of course, great inequality remains, especially in the US, but it is hard to argue that human development isn't higher here than it is in much of the developing world. That world, however, will get its chance. As the economic prospects of poorer nations improve, their labor costs will likewise increase. Perhaps there's nothing wrong with this. Everyone gets a little richer, the labor cost differential among nations decreases, and competition derives solely from innovation. There you go. You've reached the first Utopian plateau.

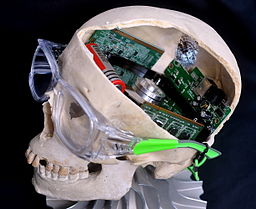

Developed nations, however, are not willing to sit back for the next century and hope that this scenario unfolds. They are fighting back with their own reductions in labor cost. Though China passed the US in total industrial output in 2010, the US still maintains a significant lead in per-capita productivity (though it is second to Japan in this regard). While the US is paying its factory workers more, it is also getting more product from fewer people. Are Americans working harder? No, you know what I'm talking about. It's not the people that are working harder, it's the machines. Automation is a great strategy. You as a nation have a choice. You can compete with cheap labor, which if you're successful will only result in that labor becoming more expensive. Or you can compete with ever more sophisticated machines, which will only get less expensive. The guy with the first plan doesn't really stand a chance against the gut with the second one. If developed nations, and the US in particular, capitalize on their lead in automated production and distribution, it could put them back at the head of the pack.

That seems great, except for all the people in the unemployment lines. Who really wins in this scenario? In the short term, it's the people who own a stake in manufacturing profits more than it is everyday citizens. Those folks are off in search of jobs at Bertucci's. For example, consider this story (anecdotal though it is):

Louisville factory: 100 printers, 3 employees

Or this one:

Robots Threaten These 8 Jobs

Now wait a minute. What year is this? 1930? Am I sounding like one of those doomsayers who predicted the fall of civilization when industrialization hit the heartland, replacing all those farmhands with the giant bug-like tractors from the Grapes of Wrath? One might argue, this is just another stage in economic progress. Most of the US population worked on farms in 1900. Only a few percent do now. We were fine because we created new industries. Namely, we created the new industries that are following the path of farming in the twentieth century and firing all of their workers. What's the next stage? They say it's the knowledge economy. There is, however, a significant difference between the knowledge economy that is replacing the industrial one and the industrial economy that replaced the agricultural one. Most people who participated in the farming economy could also participate in the industrial one. That was true in the US a century ago and it is true in China now, where millions have migrated from the farmlands looking for work in the country's manufacturing centers. Not everyone can participate in the knowledge economy, however. The problem is only exacerbated by the lack of political will to develop the human resources we already have.

Is the solution to go Amish and decide that we should halt automation at a certain point? Perhaps if the major industrial powers would just get together and agree on a technological target that allows full employment? Ah, global socialism... However, there is this other problem with development. It usually leads to lower birthrates and longer lifespans. Even if it were possible for everyone to agree on a way of keeping the world employed at a certain level, it's natural to assume that a part of the deal would be similar standards of living across that economic bloc. Many developed countries are struggling with stagnant or declining populations, along with aging demographics. Even in the US, which has a higher birthrate than many of its Western piers, population growth is really driven by immigration. That trend is especially pronounced at the younger end of the population. This would imply that perhaps automation is a good thing in the long run. Machines can replace the young workers we aren't making anymore and reduce living costs for older people who can't work as hard as they used to. Maybe machines can even take care of us in our golden years. Maybe, just maybe, we can drive production costs down to zero. In that scenario, where every lick of farmed or manufactured product comes from the hands of our robot friends, we don't have to worry about jobs. Everything costs nothing. Wouldn't that be great?

Well, in the short term it would be a painful transition for many generations. In the long term it would probably destroy us all. Assuming such a thing were even possible, the transition to a zero cost, fully automated economy would take longer and produce far more upheaval than the more incremental transitions we've seen so far. Social unrest would be inevitable, putting the whole experiment in jeopardy. But suppose that we survived this stage, as we probably would? Is there a light at the end of the tunnel? For a little while, perhaps. We would be sitting pretty until we reaped the consequences of everything costing nothing. For when everything costs nothing, what would stop us from having everything? That is the moral of this rather long winded story. Even now, where production costs are far from zero, the decrease in costs has lead to a natural increase in demand. If this trend should continue, it may well lead to environmental ruin before we ever get to the time when everything is free. Hiding behind the story of competing economies and hand wringing over employment figures is the story of consumption. To me, that's a pretty scary story. It would be easy to say that we should consume less. Honestly, we probably should. I tend to believe that once they've achieved a certain level of comfort, most people would be happier without the burden of more stuff. Apologies for the blanket generalization, but deal with it because chances are I'm right on this one. However, it is hard to separate that "certain level of comfort" from the overall economy. Good food, good healthcare and good schools exist in the same world as high end phones and luxury cars. It may not be possible to have one without the other. Consumption seems to be the only model we have to support any kind of standard of living above that afforded by subsistence farming or hunter gathering. I'm not advocating a return to that way of life by any means.

That is where this ends, with no solution. I leave that as an exercise for the reader.

In The Meantime, There's More To Read

No comments:

Post a Comment